The Fuliru people (also spelled Fuliiru) are a Bantu ethnic group native to the South Kivu Province in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Historically, they have inhabited the Uvira Territory, where they represent the largest ethnic group within the Bafuliiru Chiefdom — a traditional authority that holds central and northwestern regions of Uvira.

Over time, the Fuliru expanded their presence to the Ruzizi Plain, a fertile lowland area located in the northeastern part of Uvira, near the borders of Rwanda and Burundi. Within this Ruzizi Plain Chiefdom, the Fuliru people form the primary demographic base, and several Fuliru communities can still be found today living close to, or interacting across, those international borders.

Their territory is traditionally rural and agrarian, with strong cultural roots tied to chieftaincy systems, clan-based leadership, and agropastoral livelihoods. The Fuliru are known for their resilience, structured society, and cross-border historical relations with neighboring ethnic communities including the Bavira, Bashi, Vira, and Barundi.

Fuliru people

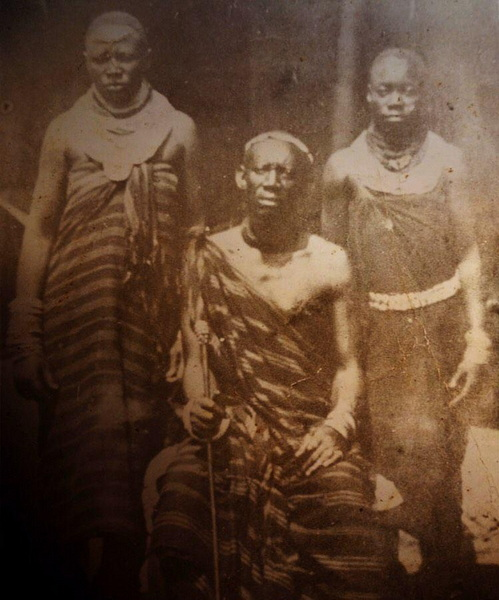

Fuliru grandmother and her granddaughter in Lemera, Bafuliiru Chiefdom

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 615,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Kifuliiru, Kiswahili, French, and English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Fuliru Religion, Islam, and Irreligious | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Vira, Nyindu, Bashi |

| Person | Mufuliru |

|---|---|

| People | Bafuliru |

| Language | Kifuliru |

| Country | Bufuliru |

🟦 Demographics, Language, and Socioeconomic Life

According to a 2009 national census, the Bafuliru population was estimated to be over 250,000. Earlier estimates from 1999 placed the number of Kifuliiru language speakers at approximately 300,000, highlighting a strong retention of linguistic identity despite decades of regional instability.

The Kifuliiru language, part of the Bantu subgroup within the larger Niger-Congo language family, is closely related to other regional tongues such as Vira, Shi, Havu, Tembo, and Nyindu. The language plays a key role in maintaining the Fuliru cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and intergenerational continuity.

Occupationally, the Fuliru people are primarily subsistence farmers and livestock herders. They cultivate crops such as cassava, maize, beans, and bananas. In addition to farming, the Bafuliru are widely recognized for their artisanal skills, especially in pottery and basket-weaving. Their handcrafted baskets serve multiple purposes — from food storage to interior decoration, and even as musical instruments during traditional ceremonies.

However, like many other communities in Eastern DRC, the Fuliru continue to face significant socioeconomic challenges. These include limited access to clean water, basic healthcare, formal education, and infrastructure. Land conflicts are particularly prevalent due to overlapping claims between indigenous populations and incoming communities, often resulting in displacement and intercommunal tensions.

Additionally, Fuliru women and girls remain highly vulnerable to sexual and gender-based violence, a crisis exacerbated by ongoing armed conflicts, militia activity, and a culture of impunity that dominates the region. These violations not only harm the individuals directly affected but also deeply undermine the community’s long-term social and psychological resilience.

Bafuliiru Chiefdom

Colonial Chieftaincy System in the Belgian Congo

At the onset of Belgian colonization of the Congo, the establishment of chieftaincies emerged as the primary system of governance used by the colonial administration. This method sought to uphold a structure that respected local customs and traditions, while also imposing control through what was known as indirect rule.

To ensure governance did not violate long-standing ancestral norms, the Belgian colonial administration defined three core criteria for the establishment of any chieftaincy:

1. The presence of a recognized customary authority.

2. A well-defined territory occupied by the community.

3. The recognition of the community as a distinct ethnic or tribal group.

These conditions were intended to prevent lawlessness and uphold traditional legitimacy. Consequently, wherever these three criteria were met, a chieftaincy (chefferie) was created, often accompanied by the appointment of a traditional leader (chief or chef de groupement) charged with maintaining public order and managing local affairs.

However, ethnically mixed regions presented a significant challenge. In areas with co-existing or competing ethnic groups, the decision on who should be appointed as chief often sparked tensions, power struggles, and at times, even violent conflicts. Belgian administrators had to navigate complex sociopolitical dynamics, which sometimes led to favoritism or the imposition of authority on groups that had no historical leadership structure of their own.

To formalize their strategy, the Belgians allocated each ethnic group—no matter how small—its own administrative entity. This could be a chiefdom, sector, or a groupement (small grouping), all considered local administrative units. These administrative zones were intended to align with tribal or clan-based geographies. However, this process led to extreme fragmentation.

For example, the former Orientale Province, which encompassed what is today Haut-Congo and the former Kivu region, became subdivided into over 2,500 chiefdoms and groupements. This intense level of subdivision, while intended to simplify governance through traditional structures, ultimately created serious administrative inefficiencies.

This colonial tactic fell under the broader umbrella of indirect rule, wherein the colonizers governed through local leaders rather than direct European officials. On paper, it preserved native authority, but in practice, it bound traditional chiefs to the colonial system, making them responsible for tax collection, public discipline, and enforcing Belgian orders. Over time, many of these leaders lost legitimacy in the eyes of their people, as they were increasingly seen as tools of colonial repression rather than defenders of indigenous values.

Furthermore, the proliferation of artificial chiefdoms often disrupted ethnic cohesion. Ethnic groups were split between administrative zones, while others were merged without regard to cultural or linguistic unity, planting seeds for future ethnic and territorial conflicts.

Geography and Settlement Structure of the Fuliru and Neighboring Ethnic Groups

The Bembe and Buyu ethnic groups were historically grouped in the Fizi Territory, which was administratively subdivided into five sectors: Itombwe, Lulenge, Mutambala, Ndandja, and Tanganyika.

In contrast, the Bafuliru Chiefdom, located in Uvira Territory, borders both Rwanda and Burundi through the Ruzizi Plain. This plain is characterized by sandy soil that is highly favorable for growing crops such as groundnuts and cotton. Key agricultural zones in this region include Luvungi, Lubarika, and Luberizi.

The Fuliru collectivity is geographically split into two main zones:

Middle Plateau The Middle Plateau stretches between Luvungi and Mulenge, rising gradually from an elevation of 100 meters to 1800 meters above sea level. It encompasses several groupements (community clusters) and villages, such as:

• Namutiri

• Ndolera

• Bulaga

• Langala

• Bushokw

• Bushuju

• Butole

• Lemera

• Bwesho

• Katala

• Mulenge

This plateau is an agriculturally rich zone, well-suited for cultivating:

• Cassava

• Coffee

• Bananas

• Beans

• Maize

High Plateau

The High Plateau serves as a watershed between the tributaries of the Ulindi and Elila Rivers, and also feeds torrents that flow into the Ruzizi River and Lake Tanganyika. This zone is defined by its:

• Rugged terrain

• Steep slopes

• High elevations (between 1800 and 2700 meters)

Main villages in the High Plateau include:

• Kagongo

• Kishusha

• Mulobela

• Kashekezi

These villages experience a cooler climate and support the cultivation of:

• Irish potatoes

• Beans

Unlike the Middle Plateau, the High Plateau is less densely populated and primarily used for cattle grazing.

This division of land demonstrates the ecological diversity of Fuliru territory and how it influences settlement patterns, agricultural practices, and economic activities.

Bafuliiru Groupements (Groupings)

The Bafuliru Chiefdom is subdivided into groupements (groupings), each governed by grouping chiefs (chefs de groupement) who are appointed by the paramount Mwami (chief or king).

Each groupement is further divided into localités (villages), which are also ruled by customary chiefs.

The five main groupements within the Bafuliru Chiefdom are:

• Runingu

• Itara-Luvungi

• Lemera

• Muhungu

• Kigoma

Muhungu Groupement

The Muhungu groupement, one of the five administrative groupements within the Bafuliru Chiefdom, is composed of a number of villages (localités), each governed by a customary chief operating under the authority of the groupement chief (chef de groupement).

Villages by Bafuliiru Groupement Muhungu Groupement

Kabondola

Kagunga

Kaholwa

Kalemba

Kasheke

Kaluzi

Kazimwe

Kibumbu

Kasanga

Kihanda

Mukololo

Lugwaja

Masango

Muzinda

Muhungu

Namukanga

Kiriba

Butaho

Kahwizi

Kigoma Groupement

Bibangwa

Bikenge

Kukanga

Bushajaga

Kahungwe

Butumba

Kabere

Karava

Kalengera

Kahololo

Kalimba

Karaguza

Kahungwe

Kasheke

Kiryama

Kanga

Kashagala

Kasenya

Kishugwe

Kigoma

Lubembe

Kihinga

Mangwa

Miduga

Kitembe

Mibere

Kitija

Muhanga

Kabamba

Mulenge

Kaduma

Mushojo

Masango

Kitoga

Mashuba

Mulama

Kagaragara

Ndegu

Rurambira

Rugeje

Rubuga

Rusako

Sogoti

Taba

Sange

Kabunambo

Runingu Groupement

Katembo

Kashatu

Ruhito

Ruhuha

Namuziba

Kasambura

Katwenge

Bulindwe

Narumoka

Kalindwe

Itara-Luvungi Groupement

Bwegera

Lubarika

Kakamba

Murunga

Ndolera

Katogota

Luberizi

Bulaga

Luburule

Bideka

Lemera Groupement

Kiringye

Kidote

Langala

Bwesho

Mahungu (or Mahungubwe)

Narunanga

Namutiri

Lungutu

Kahanda

Kigurwe

Ndunda

Clans

Bafuliru Clans and Their Traditional Roles (Expanded Edition)

The Bafuliru ethnic group is a rich and diverse society structured around 37 historically and spiritually significant clans. These clans, also referred to as lineages or progenitor families, form the foundation of Bafuliru identity. Each clan has a deep-rooted heritage, often tied to a specific craft, role in society, spiritual duty, or leadership responsibility. The clans operate both independently and cooperatively within the Bafuliru Chiefdom, a traditional governance system recognized by the Congolese state.

Understanding the structure and significance of these clans helps to appreciate the social fabric of the Bafuliru people. Below is a detailed account of each clan, its origin, traditional duties, and relevance within the wider Fuliru community:

1. Badaka

Master blacksmiths and metalworkers essential to tools, weapons, and ceremonial artifacts.

2. Balabwe

Land stewards and dispute resolution elders with deep historical knowledge of sacred sites.

3. Bahatu

Oral historians and custodians of folklore, proverbs, and ancestral narratives.

4. Bahamba

Royal lineage. Often produce traditional rulers and control agricultural markets.

5. Bahange

Spiritual healers and ritual specialists of medicinal practices.

6. Bahembwe

Skilled pastoralists and breeders of local livestock.

7. Bahofwa

Genealogists and keepers of clan ancestry.

8. Bahundja

Elite messengers and protectors of sacred information between chiefdoms.

9. Bahungu

Ritualists for fertility and agricultural blessings.

10. Bazige

Assimilated Hutu-descendant clan known for blending cultural traditions.

11. Baiga

Forest guardians and spiritual environmentalists.

12. Bajojo

Musicians and dancers for all ceremonial and social events.

13. Bakame

Storytellers and myth-keepers preserving oral traditions.

14. Bakukulugu

Traditional builders and constructors of communal and sacred spaces.

15. Bakuvi

Salt traders along Lake Tanganyika and regional economic bridges.

16. Balambo

Guardians of royal headpieces and diadem ceremonies.

17. Balemera

Traders and political influencers, often bridging Fuliru with neighboring states.

18. Balizi

Farming innovators believed to be of Ugandan origin.

19. Bamioni

Protectors against witchcraft and mediators in ancestral conflicts.

20. Banakatanda

Matriarchal clan responsible for mwami funeral rites and royal succession rituals.

21. Banakyoyo

Guardians of peace treaties, laws, and oral records.

22. Banamubamba

Nomadic livestock keepers of traditional cattle herding routes.

23. Banamuganga

Spiritual and herbal healing specialists.

24. Basamba

Farming land preparation experts and agricultural advisors.

25. Bashagakibone

Experts in traditional embalming and mummification of nobles.

26. Bashimbi

Renowned rainmakers, beekeepers, and fisheries specialists. Their founder Kashambi is legendary for torch fishing.

27. Bashamwa

Purification ritual leaders and spiritual space cleansers.

28. Bashashu

Potters and ceremonial clay jar makers.

29. Basizi

Spiritual custodians of ancestral shrines and initiation rites.

30. Basozo

Rwandan-origin clan assimilated through intermarriage, skilled in weaving.

31. Bashago

Gatekeepers and border defenders of the chiefdom.

32. Batere

Producers of sacred brews and fire ritual tools.

33. Batoké

Fisherfolk managing the aquatic food supply and lake-based economy.

34. Batumba

Highly respected royal clan with strong traditional authority through the Mutumba ruler.

35. Bavunye

Transporters and horse dealers in traditional trade networks.

36. Bavurati

Strategists and protectors of territorial security during conflict.

37. Bazilangwe

Climate and weather ritualists responsible for seasonal ceremonies.

Conclusion: This clan-based structure is integral to understanding Bafuliru political systems, cultural identity, and traditional governance. The knowledge, customs, and roles passed down through each of these lineages help preserve the continuity of Fuliru heritage across generations.

History

Between the 10th and 14th centuries, early Bafuliiru groups branched out from what we now call the Lwindi Chiefdom. According to researcher Shimbi Kamba Katchelewa, cited in Charles Katembo Kakozi’s 2005 study, these groups forged new settlements in Mulenge, Luvungi, and Lemera—foundations of the “Hamba Kingdom,” guided by the Bahamba clan. These movements were part of expansions from the Lwalaba River basin, particularly around where the Ulindi River meets the highlands—marking the initial ascent of the Fuliru into the mountainous terrain.

Scholars debate the timing of this settlement. René Loons, a Belgian administrator, attributed the founding of the modern Bafuliiru Chiefdom to Mwami Kahamba Kalingishi arriving by the 16th century. Others, like Kingwengwe Mupe and Bosco Muchukiwa Rukakiza, suggest the migration lifted to the 17th century. Historian Jacques Depelchin reframed this movement as more of a continuing expansion, not a one-off migration—given Fuliru’s persistent ties to their original homeland well into the 19th century.

The Bahamba walked a path from Wahamba to Bafuliiru—not just a name change but a statement of evolving identity. Fuliru and Vira were famed for ironworking—so much so that the term Fuliru likely stems from the verb ku‑fula (“to forge” or “beat iron”).

As time passed, Chief Luhama strengthened central authority by dividing his realm among his three sons—Nyamugira, Mutahonga, and Lusagara—each controlling distinct zones (from plains to mountains), maintaining cohesion while responding to local autonomy demands.

The Belgian colonial state formally recognized the Bafuliiru Chiefdom on 18 August 1928. By the 1930s, authority passed to Chief Matakambo, son of Mahina Mukogabwe, and in 1940 to another Nyamugira, consolidating Bahamba leadership—though some say they displaced the Balemera, the original locals, to establish control over the Uvira region centered in Lemera.

Moving into the 19th century, the landscape changed again. Barundi groups, led by Chief Ngabwe, pressed into Fuliru lands seeking fertile territory. Territories were exchanged for ivory, escalating into conflict with Bavira neighboring groups. Chief Kinyoni, under Burundian King Mwezi Gisabo, surged invasions into Mulenge, Kigoma, Kalengera, and nearby villages. But under the heroic leadership of Katangaza of Bwesho, the Bafuliiru repelled these incursions, though Belgian backing briefly gave Kinyoni strength before his defeats.

Then came the arrival of Banyarwanda herders (Tutsis): fleeing Rwabugiri’s campaigns in Rwanda, they crossed the Ruzizi River, initially settled in Kakamba (Itara-Luvungi), and later moved to Mulenge. Instead of conquering the Fuliru, they paid grazing tribute to the mwami and engaged in mutually beneficial trade. Mulenge became known as a Tutsi enclave—“Banya‑Mulenge” (people of Mulenge).

Colonial authorities, however, never granted the Banyarwanda land rights or traditional recognition as they did to Bafuliiru. The Belgians classified citizens as either “civic” (rarely awarded) or “ethnic,” and the Banyarwanda were denied both indigenous status and traditional chieftaincy positions—unlike recognized groups like the Bafuliiru. This legal exclusion prevented their land claims from ever being validated.

This colonial exclusion and those identity measures led to deep-rooted tensions. Over decades—from 1960s migrations to civil conflicts—contested land and belonging provoked violence. Human rights reports estimate that by 1996, conflicts had claimed around 70,000 lives, deeply displacing communities and entrenching mistrust

Summary in Narrative Form:

The Bafuliiru people trace their roots to highland expansions from Lwindi into Mulenge, Luvungi, and Lemera centuries ago, laying down a centralized kingdom under the Bahamba lineage. Their identity—rooted in ironworking craft—emerged organically, as their name suggests forging strength and resilience. They organized themselves through traditional chieftaincies and royal lineages, which persisted even under colonial frameworks. Barundi and Banyarwanda incursions introduced complex dynamics—sometimes violent, sometimes reciprocal. Crucially, while Bafuliiru kept their lands and titles through colonial negotiation, the Banyarwanda, despite contributing to local economies, were systematically denied both legal land rights and traditional authority, setting the stage for prolonged conflict well into the modern era.🧭

Why the Banyarwanda Were Denied Land in Bafuliiru Territories

The question of why the Banyarwanda—comprising Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa from Rwanda—were denied land in the Bafuliiru Chiefdom and broader South Kivu region is rooted in a complex combination of colonial policies, indigenous identity systems, and socio-political tensions. While many Banyarwanda lived in the region for decades and contributed to its development, they were never granted full land rights or considered indigenous by colonial or postcolonial authorities. Several reasons explain this exclusion.

1. ❌ They Were Not Considered “Indigenous” Ethnic Groups

The Belgian colonial administration recognized tribes based on their traditional social structures. In the Congo, to be considered an indigenous tribe or “tribu autochtone”, a group had to meet certain criteria:

- Possession of a recognized paramount chief or mwami

- Longstanding ancestral ties to a defined territory

- Distinct clan structures and native institutions (like “balù” or “vakama”)

The Banyarwanda, on the other hand, did not have these structures within Congo. They were seen as migrant communities from Rwanda who had no traditional chiefs or ancestral land within the Congo basin. As such, they were classified as foreigners (étrangers) or non-native populations, and excluded from permanent land ownership or official recognition.

2. 🚧 They Were Originally Brought in as Laborers, Not Settlers

Between the 1920s and 1950s, the Belgian administration actively recruited tens of thousands of Rwandan workers—mainly Tutsi pastoralists and Hutu laborers—to work in Congo’s mines (such as Union Minière du Haut-Katanga), plantations, and Catholic missions.

These workers:

- Came under temporary labor contracts

- Were not granted Congolese nationality

- Maintained their legal ties to Rwanda

Therefore, they were not settled with the intention of permanent land ownership. They were viewed as a mobile workforce, not as communities to be integrated into Congo’s indigenous land systems. Even after decades of residence, many Banyarwanda families lacked land deeds or formal recognition.

3. 🛡️ Colonial Policies Prioritized Protecting Indigenous Land Rights

As tensions arose between Banyarwanda migrants and native Congolese tribes (especially the Bafuliiru and Bavira), the colonial state often sided with the traditional chiefs. The Belgians:

- Respected the authority of indigenous mwamis (chiefs)

- Legally recognized the ancestral land boundaries of tribes like the Bafuliiru

- Denied Banyarwanda any territorial autonomy

For example, when the Barundi (closely related to the Banyarwanda) settled in parts of Uvira, local Fuliru chiefs protested to colonial officers. The Belgian administration then reinforced the position that no land could be permanently allocated to migrants, and that only indigenous communities could administer land.

4. 🏚️ Banyarwanda Were Treated as Refugees, Not Citizens

After the 1959 Rwandan Revolution and ethnic conflicts in Rwanda, many more Banyarwanda—especially Tutsis—fled into eastern Congo. These refugees:

- Were settled in transit camps (like Lemera, Kalonge, and Mulenge)

- Were not given legal status as Congolese citizens

- Were not integrated into customary land systems

Even when Banyarwanda communities pushed for recognition as a tribe or for land titles, their claims were denied. Congolese authorities and local tribes argued that a “tribe” could not be invented overnight, and that these groups lacked:

- A recognized territory within Congo

- Historical authority structures within the country

This rejection led to deep frustration, particularly among Tutsi herders who had become economically powerful but remained landless.

5. ⚔️ Fear of Political Takeover and Regional Loyalty

Many Banyarwanda—especially Tutsis—were linked to Rwandan monarchs and aristocracy. In the 19th century, King Rwabugiri of Rwanda had expansionist campaigns that extended into Uvira and other Ruzizi regions. As a result:

- Local Congolese viewed Banyarwanda as agents of a foreign power

- Bafuliiru and Bavira feared being politically overtaken

In the 20th century, these fears grew worse as Banyarwanda elites began to demand their own chieftaincy (chefferie), and some even tried to claim that “Mulenge” was their ancestral homeland. This was seen as a fabricated ethnogenesis by other Congolese tribes.

6. 🔥 Land Disputes and Security Conflicts

By the 1990s, land tensions had escalated into armed conflicts:

- Indigenous groups like the Bafuliiru accused Banyarwanda of land grabbing

- Banyarwanda militias were formed, some aligned with Rwanda

- Groups like CNDP and M23 emerged, deepening mistrust

The long history of landlessness, political marginalization, and cultural exclusion helped radicalize some Banyarwanda youth. In response, native Congolese strengthened their opposition to granting any land rights to Banyarwanda populations—viewing such actions as a threat to territorial sovereignty.

🧾 Conclusion: A Complex History of Exclusion

The Banyarwanda were denied land in Congo not because of their ethnicity alone, but due to a combination of:

- Colonial policies that treated them as foreign laborers

- Absence of traditional authority structures within Congo

- Resistance from indigenous tribes who feared losing ancestral lands

- Tensions arising from historical Rwandan expansionism

- Security fears linked to recent rebellions and conflicts

Even today, the issue of land ownership and ethnic belonging remains one of the most sensitive in eastern DRC. Understanding this context is essential to grasping why the Bafuliiru Chiefdom—and many others—have refused to recognize Banyarwanda as indigenous landholders.